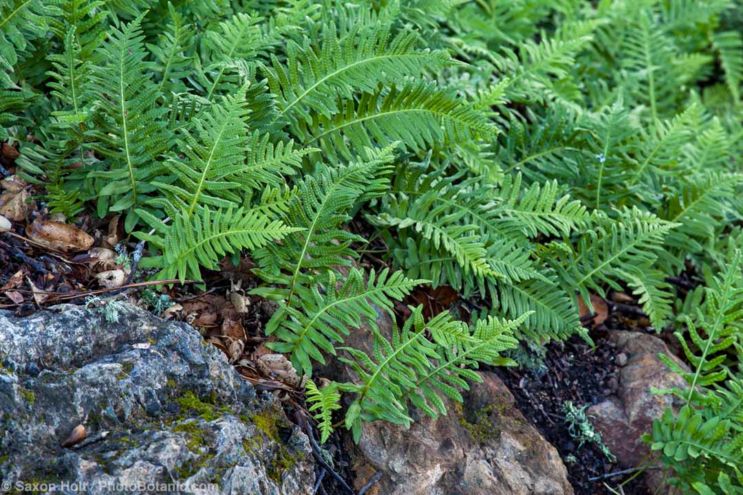

Guaranteed to lift your spirits on the dreariest of winter days, summer-dormant Polypodium californicum (California polypody) appears suddenly with the first fall rains, remains a lustrous bright green until mid-spring, and then just as suddenly dies back to the ground leaving barely a trace.

Polypodium californicum in University of California, Berkeley, Botanical Garden

Native to coastal California and northern Baja California, Polypodium californicum is usually found in shaded canyons, on streambanks and north-facing slopes, and on rocky cliffs and bluffs within or near the summer-fog zone. A volunteer in my northern California garden, it has reappeared reliably among the rocks of a dry-stacked wall for the forty-plus years I’ve gardened here.

Several other polypodiums are dormant in summer and thus good candidates for summer-dry climates. Polypodium glycyrrhiza (licorice fern) is another that shows up with fall rains and cleanly disappears as days turn hot. A coastal native from southeastern Alaska to central California, it spreads slowly by means of a creeping rhizome. P. glycyrrhiza is often epiphytic, establishing itself on mossy ground or on the moss-covered trunks of bigleaf maples.

Polypodium calirhiza in University of California, Berkeley, Botanical Garden

As its name suggests, Polypodium calirhiza (nested polypody) is a natural hybrid of P. californicum and P. glycyrrhiza. Native to rocky outcrops from southwestern Oregon to northern Mexico, it is summer-deciduous if conditions are dry but can be evergreen in moist environments.

Polystichum munitum (western sword fern) is an evergreen coastal native that thrives in bright shade with little or no summer water. This accommodating fern can reach 4-6 feet tall and wide in cool, damp forests of the Pacific Northwest. In my garden, with almost no encouragement, it tops out at half that size. Old fronds remain on the plant, flatten out, and turn a not unattractive russet brown. I leave these for the striking contrast they provide beneath the current season’s upright and arching, rich green fronds.

Polystichum munitum in California native garden

Pellaea mucronata (birdfoot cliffbrake) is native to dry, rocky soils in the mountains, canyons, and desert washes of Oregon, California, and northern Baja California. This is a small fern with 1- to 2-foot long fronds bearing widely spaced, rounded-oval, bluish green leaflets on stiff, purplish black stems. Dormant in summer if grown dry, it can be evergreen with occasional water. P. andromedifolia (coffee fern) is similar but said to be somewhat less dry-adapted.

Pellaea andromedifolia

A surprising number of ferns are native to arid or semi-arid climates. These usually display one or more adaptations to xeric conditions, such as small leaflets with reduced surface area, thickened or curled-under leaflet margins that protect the spore-producing sori, an overall silvery gray-green coloration, or leathery, hairy, scaly, or waxy leaflets and stems for photoprotection and reduced water loss.

Myriopteris lindheimeri (Lindheimer’s lip fern) is a small, evergreen, silvery gray-leaved fern native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Usually less than a foot tall, its leaves are divided into many small, beadlike segments with rusty brown hairs on the lower surfaces.

Myriopteris lindheimeri in University of California, Berkeley, Botanical Garden

Other garden-worthy xerophytic ferns are Myriopteris covillei (Coville’s lip fern), with green leaves divided into overlapping, rounded leaflets with rolled-under margins and scaly undersides; Pellaea truncata (spiny cliffbrake) with spine-tipped, gray-green, oval leaflets with rolled-under margins; Astrolepis sinuata (wavy cloak fern) with sage green fronds that are creamy white on the undersides; and Notholaena standleyi (Standley’s cloak fern), with triangular fronds that curl up in a ball when conditions are dry, unfurling when water becomes available.

These xerophytic ferns are native to mid-elevations of desert mountains in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, often in rock crevices or among boulders that provide some protection from hot sun. They typically require porous, well-drained soil, bright light, and good air circulation.

Desert ferns can be slow to establish in the garden, and most are not readily available, even from specialty nurseries. They may become more available if enough gardeners continue to ask for them. Meanwhile, your best bet may be plant sales of botanic gardens with desert native sections.

This is a great post. I live in Davis and would love to plant more dryland ferns, but it’s very hard to find the truly xeric species. Nurseries, here’s a niche that begs to be filled!

Thanks for your comment! I would love to see more dryland ferns become available.

Nora

Fascinating and inspiring!

A question – is the Western Sword Fern averse to growing beneath CA live oaks? I have a small group of them beneath a large oak but the ferns have never thrived. They get some additional summer water, and late afternoon sun.

Thanks very much for your terrific work and for creating this community!

Karen O in Saratoga, CA

Hi Karen,

That is such a great question. I have western sword ferns growing under coast live oaks, under big leaf maples, and under buckeyes. Those under native oaks actually do not do as well as those growing almost anywhere else, but it had not occurred to me to investigate why. I’ll see what I can find out. Meanwhile, maybe others have insights on this to share?

Nora

Interesting to hear your experience might confirm this! I’ll be interested to see if you learn anything. Meanwhile future platings might not go under oaks.