Some Mild-Winter Summer-Dry Sumacs

Share This!

Sumacs are current or former members of the genus Rhus, notorious for those species that spread aggressively by suckers or by seed (e.g., staghorn sumac, African sumac) as well as for those that through mere touch can bring on a ferocious rash (poison ivy, poison oak). Yet there are well-behaved and beneficent sumacs too. Several of these are exceptionally fine shrubs native to mild-winter, summer-dry southern California, Mexico, and parts of the American southwest. Unlike most sumacs, these are evergreen.

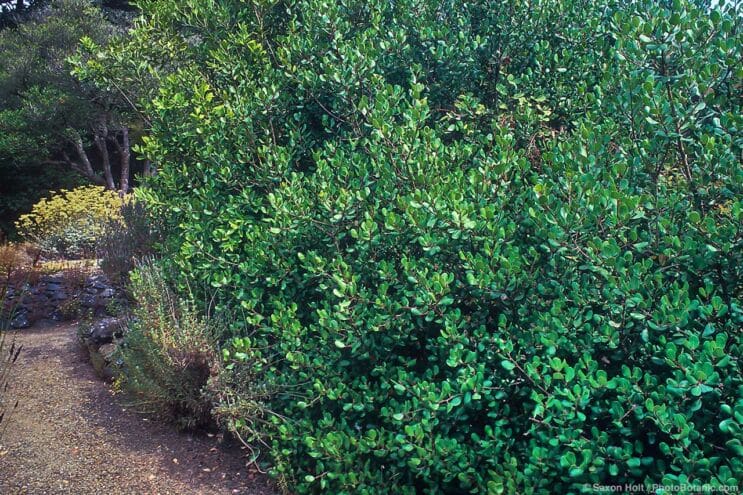

Rhus integrifolia, lemonadeberry or lemonade sumac

Rhus integrifolia, lemonadeberry or lemonade sumac, is 8-10 feet tall and 10-12 feet wide, sometimes considerably larger. Two-inch, oval to oblong leaves are thick, leathery, and glossy dark green, paler beneath, sometimes with toothed margins. New leaves are bright green and young stems and petioles are reddish.

Dense clusters of tiny, white or pale pink flowers with green bracts appear at branch ends, typically from February through May. Flowers are followed by somewhat flattened, bright red, sticky drupes. R. integrifolia is native to coastal bluffs and canyons in southern California and northwestern Baja California, usually at low to mid-elevations and often on north-facing slopes.

Rhus ovata, sugarbush or sugar sumac

Rhus ovata, sugar bush or sugar sumac, is similar but naturally occurs farther inland in semi-arid climates that are hotter in summer and colder in winter. This shrub is often found on south-facing slopes from southern California and southwestern Arizona south into Baja California Sur.

Leaves of R. ovata tend to be larger than those of R. integrifolia with smooth margins and are often folded upward along the midrib. Leaf petioles and young stems are maroon. The small, pinkish white flowers have reddish bracts instead of green and usually appear a little later. The drupes are smaller and more round. R. ovata and R. integrifolia are closely related and tend to hybridize in gardens and in the wild where their ranges overlap.

Rhus lentii, pink-flowering sumac

Rhus lentii, pink-flowering sumac, is usually smaller than R. integrifolia and R. ovata but still a substantial plant, 6-8 feet tall and 8-12 feet wide. Leaves are pale bluish gray-green with prominent yellow-green veins and midribs. Showy clusters of bright pink flowers appear in late winter to early spring and are followed by round, red drupes. This shrub is native to maritime bluffs and canyons in the western Vizcaino desert of northern Baja California Sur as well as on several of the Channel Islands.

Malosma laurina, laurel sumac

A taxonomically related plant, laurel sumac (Malosma laurina, formerly Rhus laurina) at maturity can reach 10-18 feet tall and wide. The large, broadly lance-shaped, glossy green leaves have reddish veins and stems and are folded along the midrib. New leaves and stems are bright red. The tiny, creamy white flowers with green bracts form large, dense clusters at the ends of branches in late winter and spring.

Fruits of laurel sumac age to creamy white and dry to dark brown, remaining on the plant for months if not consumed by wildlife. This shrub is native to dry, often north-facing slopes and canyons along the coast from Point Conception in Santa Barbara County south to the border between Baja California and Baja California Sur and intermittently south to La Paz.

Rhus integrifolia makes an effective large screen or unsheared hedge.

If you plan to include any of these shrubs in your garden, it’s important to remember that, although initially slow-growing, they can become very large over time. With annual light pruning R. integrifolia can be maintained at almost any size and shape, from a low groundcover to a small tree, or even espaliered against a wall.

Rhus ovata seems less tolerant of regular pruning but can be trained as a multitrunk tree or even occasionally cut back hard. Adapted to surviving wildfire, these chaparral shrubs usually can resprout from the crown after fire but resprouting after cutting back to the base is not guaranteed.

Plant these shrubs in full sun or part shade in almost any well-drained soil and provide for good air circulation. Little to no water is needed in summer but do water occasionally in winter if rains fail.

All of these shrubs are at least somewhat sensitive to low temperatures. Malosma laurina thrives only where frosts are rare or nonexistent and will die in extended freezes. Of the three Rhus species R. ovata is the hardiest.

Share This!

Related Articles

By: Nora Harlow

By: Nora Harlow

By: Nora Harlow